The Line Drawer

The Unlikely Rise to Fame (of sorts)

of a Humble Line Drawer

In the years following the end of World War One—referred to at the time as The Great War, which really wasn’t such a great idea—there was an explosion of a different kind, that of artistic creativity.

Modern art was already making itself known prior to the war with the development of abstract art by Kandinsky, Picabia, and Piet Mondrian, among others. You had movements such as Expressionism, Cubism, Fauvism. And there was Futurism, an influence on Art Deco, Surrealism, and Dada, which children learn to say at an early age, just to name a few. Besides all the other “isms,” that period also produced the Bauhaus, which has no “ism” at the end but it does rhyme with mouse. So, aside from a couple of exceptions, you had “isms” flying everywhere. Metropolitan areas in Europe and the Americas were crammed full of “isms.” Artists, critics, and collectors everywhere were a-quiver with multiple “ism” orgasms.

Among the millions of people residing in New York City at that time, there lived a humble orphaned sixteen-year-old lad who worked at a stable near the Hudson River. During the day and into the late evening, he was usually busy grooming the animals and cleaning up “horse apples.” One day, early in the Fall of 1919, one of the carriage drivers fell ill and there was no one else to pick up the slack over at Central Park. So the livery manager reluctantly sent the young stable hand to fill in and do his bit for the company. That stable hand was none other than Linus Lemming.

The world today doesn’t make sense,

so why should I paint pictures that do?

~ Pablo Picasso

“Who the hell is Linus Lemming?” you may ask. And rightly so, because he is one of the great unsung heroes of all modern art. Influences of his ground-breaking form of art are to be found in almost every corner of the world. And yet Lemmy, as he was known to a couple of tramps near the stables, went on to be forgotten by time and the great art wheelers and dealers.

On that fateful day, however, when Lemmy took hold of the reins and started working the tourist route through Central Park – a place he hardly knew – chance entered his life in a big way. Not only was he able to drive his own, albeit temporary, rig, but he was also thrilled to be in the company of his favorite mare, Hilda. She of the long, chestnut brown mane and flirtatious eyes. But we won’t get into that now.

One of his first fares that day was a pair of older gentlemen who seemed anxious to get out of the hustle and bustle of the New York streets and go for a quiet ride through the park, where they could discuss business in a civilized manner. Lemmy greeted the two men, and as soon as they were comfortably seated, he gently tapped Hilda on the shoulder with the buggy whip and she immediately set off on her accustomed route through Central Park. She was one of the older horses, and she seemed to enjoy that, unlike some of the other drivers, Lemmy was her friend and he allowed her to slowly amble at her own pace. Besides, the two businessmen were oblivious to Hilda’s pace, as they were engaged in a heated debate involving contractual issues for several forms of art “isms.” During the ride, Lemmy politely eavesdropped as best he could over the rhythmic clip-clop of Hilda’s leisurely stride.

Lemmy didn’t understand much of what was being said because some of it was in a foreign language, Bolshevik possibly, he thought. But by the end of the ride, Lemmy had garnered enough to feel inspired and afire with a new passion. A passion to create art. Whatever that was.

During that night, and many nights thereafter, as he slept in his accustomed manger, his dreams often took him to scenes in which he might someday join some of the world’s great artists and “ism-ists.” And although the only art he actually ever saw was on billboards and in waterfront bars, where there was the odd copy of some European painting or a “naughty” poster, he still felt he had something within him that could perhaps add one more “ism” to the art world. Surely the world could use at least one more, and he would be the one to do it.

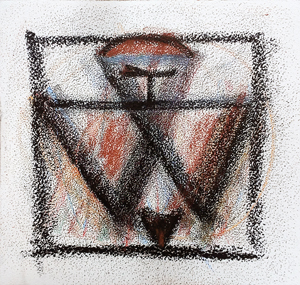

The above piece circa 1920 is titled “Woman with Large Breasts and Bushy Vagina” and is from Lemmy’s Picasso-ism period. It is believed that he was inspired to do this work by one of the “naughty” posters he had seen in a downtown bar. And even though he’d never met him, Lemmy greatly admired Picasso not only for his innovative approach to art and lovely striped sailor shirts but also as an exemplar of humility and selflessness.

With great resolve, he started frequenting the more bohemian and artsy bars of lower Manhattan. Places where he could overhear and perhaps pick up a few ideas from the aspiring starving artists of the day. And perhaps even make some friends. Thus on his half-day off each week, which was usually a Thursday evening, he would bathe in the water trough and don his best spare ragged clothing and head off to learn about art and the world of “isms.”

Although Lemmy never did manage to make any new friends or get into any of the discussions that were flying furiously over copious amounts of beer and liquor, he nevertheless managed one night during one of his forays into the bohemian haunts to overhear some artists in a bar talking about an interaction between some old fellow named Daygah and another, even older fellow Aaaang. It seems the two had met late in the previous century, and this Aaaang fellow told the Daygah chap to “Draw lines, young man, many lines.”

Lemmy, being completely soused at the time, took that admonition to heart and came to the sudden realization that this was his true life’s calling. That must be the secret to becoming a great artist, he thought. To draw lines. So that very night, on his way back to the stables, he resolved to get himself some paper and a pencil at once – in this case, stealing them from a local newsstand. And night after night thereafter, by the light of an old kerosene lantern, he would teach himself how to draw lines. He now felt that he, Linus Lemming, would someday become a great and famous “ism-ist.”

Over time, Lemmy practiced and drew line after line on the many sheets of paper he was able to steal. He even used some of the fragrant horse apples as a medium to draw with. On occasion, he used charcoal from nearby refuse fires that were lit in old empty oil drums. Eventually, he was able to get his hands on some coloring pencils, which he bought on the cheap from some pickpockets with whom he had become acquainted, who were always eager to help his artistic development.

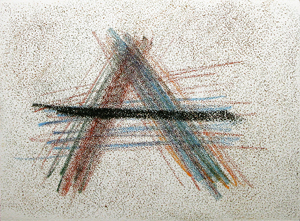

A work made around the early twenties from an uncompleted series of alphabet pieces, executed while Lemming was again unsuccessfully trying to learn writing. Due to a pressing work schedule, however, he never quite managed to get beyond the letter “A.” The piece is simply titled “Alpha.”

Lemmy practiced all forms of lines. Thick ones, thin ones, straight, curved, even dotted and dashed lines. Soon, with the assistance of his new acquaintances, he began to use supports other than cheap scraps of paper. They were able to procure for him the odd leftover roll of canvas or sturdy sheets of various art papers. But this wasn’t enough. Lemmy now felt he wanted the world to see his lines, which up until now he had only shown to his street acquaintances, and of course, Hilda. She was a great admirer of his work.

Then one day, Lemmy’s opportunity arrived. In the Spring of 1923, a local lady who was an art enthusiast of some modest means and influence convinced the nearby Fire Station Captain to put on an exhibition of children’s and others’ drawings and paintings. The word went out, and posters were hung in various places throughout the neighborhood. Unfortunately, Lemmy had never learned to read anything but the words “Danger” and “Stop,” as he came across them quite frequently in his workplace. He sort of learned to spell out his name but preferred the simpler form of using just “LL” to sign his works. He hoped that in the not-too-distant future, the world would come to know the greatness of “LL-ism,” or maybe just plain “Lism.”

Fortunately for Lemmy, while he was brushing one of the horses outside the stables, one of the corner “newsies,” or newspaper sellers, was barking out the advertisement for the upcoming art exhibit at the Fire Station. At hearing this news, Lemmy grew very excited. He spent the next couple of nights going through his collection of drawings, and with the astutely critical eye of Hilda as help, with great hope, the two of them selected four of the best drawings for submission to the show.

Much to his surprise, all of Lemmy’s line drawings were accepted for the Fire House exhibit. It didn’t really matter to him that there were only five other applicants. That left plenty of room on the walls for all the submitted works.

At the show, his work was noticed by the local patroness, who had brought along an art dealer friend of hers. The dealer didn’t immediately appreciate Lemmy’s work, but he humored his lady friend and purchased all four drawings for the amazing sum of twelve dollars, which was good money in those days. Especially for a person in Lemmy’s position in society.

This experience spurred Lemmy into being even more aggressive with his creativity, and he drew lines like no one else. His new patroness, an elderly widow, would support him by periodically purchasing some of his drawings, a practice that gave her something to look forward to. Her name was Sylvia Tuttle, of the West Side Tuttles – an old and honorable family of which, sadly, she was the last member.

Madame Tuttle began to occasionally have Lemmy over for tea to meet some of her other widowed friends, most of whom did not have very good eyesight by that point but were eager to help out Lemmy by purchasing his art. And Lemmy, to return the invitation, introduced Madame Tuttle to Hilda. It is reported that the two females hit it off well.

Then, under the tutelage of one of Widow Tuttle’s friends, Lemmy was introduced to and studied lines under some of the greatest line masters of his time in New York, including the Asian master line-drawer and noodle maker Ho Li Phong. Sadly, Ho was yet another of those great masters who were destined to remain unknown to the world at large. But he did gain some renown in Chinatown for his Dim Sum platters and his signature dish of delicate Chinese noodles with roasted duck.

This unique work is the only known surviving piece from the period during which Linus Lemming was experimenting with curved lines. It is reported that he was inspired by the udders of his favorite and only cow friend, Magnolia, or Maggie for short. She provided fresh milk for the stable hands and crew for the daily gruel that sustained them all through long hours of drudgery.

From Madame Tuttle’s living room, the news spread among the older “gentry” of the area, who also eagerly purchased Lemmy’s line drawings. Now that Lemmy was earning quite a bit more than he was accustomed to, he quit his day job at the stable to devote all his time to his art – although he continued to faithfully visit Hilda. He could now afford a small apartment of his own. He also soon came to the conclusion that in order to become better known, he needed to go bigger. For was bigger not better?

Again with the help of his street acquaintances, Lemmy was able to procure some very affordable oil paint that was normally used on house exteriors, and in the thick of night, he would go out onto the streets of the West Side, brush and bucket in hand, and paint lines in the streets, most of which were still of granite cobblestone – a texture that only added to the effect of Lemmy’s lines.

First, he started by painting long straight lines down the middle of the street so that no one would miss them. Then he began to get a little more abstract and painted dots and even long dash lines. At this point in his career, he would often hire one or two young lads to help him with his stealthy artwork process. Pretty soon, large swaths of several neighborhoods had lines drawn along the sides and down the middle of the streets. But there was also a method to his madness. Lemmy soon realized that horse carriages and even the new automobiles would follow his painted lines and almost always stay within them. He even began to paint curved lines and diagonal lines at intersections, including on streets where trolleys and buses ran.

Since the local constabulary found that Lemmy’s lines made their traffic control work easier, no one complained. In fact, many a policeman quietly urged him on. Lemmy’s line art was methodically organizing the city streets. Word eventually got to the mayor’s office, and Lemmy was hired to organize teams of men who would copy his art style and use it throughout the city. And although it was rumored that something similar was being done near Detroit, Michigan, it was nowhere near the scale and quality of Lemmy’s style. And thus, “Lism” was born.

Once news of the amazing and utilitarian “line art” reached the Governor in Albany, he called for a special session of the State Senate, in which they unanimously agreed that all the roads of New York State would ostensibly become an enormous sprawling canvas for Lemmy’s new style of art. Soon other states would follow. And offers for commissions from foreign nations also flowed in. It was at this point in his career that Linus Lemming had realized his dream of spreading a truly noble and useful “ism” for the good of society and the world at large. Lemmy’s “Lism” was now literally on the world map.

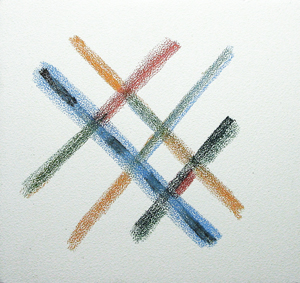

“Street Plaid” is also from the early nineteen twenties. It exemplifies the minimalist foundations that would propel Lemming on his grand plan to paint the streets. One can see elements of what would eventually become standard components of his signature style, the highly refined lines, and dashes.

During this highly profitable and productive period of his career, Lemmy still experimented and began to go to museums and galleries to see and learn from other artists – some of whom he came to admire. One of his most cherished memories was the time in the winter of 1947 – after yet another big war – when he was living in Greenwich Village, and one night while checking out the art scene he wandered past the now-famous Cedar Tavern. Suddenly out stumbled a drunk who slammed into him and vomited all over Lemmy’s new winter coat. But being the mild-mannered and generous person he was, instead of getting angry over the event, Lemmy simply helped the man over to the curbside and leaned him up against several other fellows in a similar state who were sitting together on the sidewalk, huddled against a parked sedan. Within moments of this humble act, he learned from one of the fellows smoking outside the tavern that the man he’d just helped was a fellow by the name of Jackson Pollock.

Listening to his intuition, Lemmy went home to his now larger apartment and draped his soiled overcoat on the radiator to dry overnight. Being somewhat familiar with Pollock’s work, Lemmy couldn’t help but notice the similarity between the man’s painting and his projectile-vomit style. Needless to say, Lemmy had that overcoat preserved by an art conservationist and saved it till his dying day.

That day came when, ironically, Lemmy was accidentally hit in the head by a spooked police horse while crossing 8th Street. Worst of all, upon Lemmy’s untimely passing in 1964, all of the works that were to be found in his apartment were appropriated by someone claiming to be a “cousin” of his. Gone also is the original Jackson Pollock vomit-painted overcoat.

Fortunately for posterity, some of Lemming’s earlier works that were in the possession of collectors or their heirs have managed to survive. And during the hedge-fund frenzy of the 1980s, an anonymous billionaire art collector purchased from the City of New York a whole intersection that was hand-painted by Lemmy in his early days. As it was one of the few remaining cobblestone streets in the city, conservators were able to methodically remove, number, and catalog each cobblestone before reverently rebuilding the street intersection just beyond the Olympic-size swimming pool within the confines of the collector’s hidden über-mansion somewhere in the wooded hills outside Greenwich, Connecticut.

Around the same time, rumors were flying that MOMA was also in negotiations with the City to acquire a different section of Lemmy’s street art, though apparently chose not to pursue it. Perhaps they didn’t have the space and funds available for such an extraordinary and truly incomparable modern “ism” – an “ism” that covers within its scope a plethora of other “isms,” like conceptualism, minimalism, and modernism, to name just a few. To this day, even though most people are oblivious to it, “Lism” connects and supersedes all the other “isms” in its global reach and practical benefit to humanity.

♦

Editor’s Notes:

Art Twerks is proud to exhibit for you a small sampling of surviving works attributed to Linus “Lemmy” Lemming from various stages of his artistic development. The works shown are all small in size but big in concept. Although there are no known surviving photographs or images of Linus Lemming, the Art Twerks research team is hard at work following up on baseless rumors relating to the possible existence of old photos of Mr. Lemming, and even one report of some surviving early movie footage of the artist at work. Should any discovery of this nature materialize, we will post it on our website immediately. In the meantime, in the spirit of full disclosure, the 4 artwork samples attributed to “Lemmy” on this page are actually the creation of artist Nikitas Kavouklés.

♦

Drawings on this page © Copyright 2017 Nikitas Kavouklés, All Rights Reserved